Milam County Historical Commission

Milam County, Texas

Milam County, Texas

A True Christmas Miracle — 100 Years Ago

by Mike Brown - Reporter Editor

Rockdale Reporter - December 19, 2013

Rockdale Plumber Saved 44 Lives in Devastating 1913 Brazos Flood

Christmas season “miracles” come from a variety of sources, but for 44 flood-stranded victims of the Brazos River 100 years ago one came from Rockdale.

Walter Suess, a Rockdale plumber, launched a light skiff into the roiling six-mile-long lake that had mostly consumed the community of Valley Junction, and brought them to safety.

The flood, together with the iconic 1921 event eight years later, is regarded as one of the two worst in Milam County history.

“Walter E. Suess, an humble citizen, quietly stepped forward when all others held back in awe,” Reporter Publisher John Esten Cooke wrote. “(He) placed his life in jeopardy when others more dangerously situated might be saved.”

The Gause area flood had already claimed the lives of three men, one of them Henry Martin, the vice-president and general manager of the International & Great Northern Railroad.

Martin had brought his personal rail car to the area to direct rescue operations.

Two Gause men, Willie Roberts and Tim Lee, drowned in a separate attempt to launch a boat into flood waters to rescue the dozens of persons in peril at Valley Junction, just across the river in Robertson County.

MAROONED - The central U. S. had already experienced a history-making flood on Easter Sunday, 1913, but in Texas the fall and winter were worse.

Several smaller floods had already been covered in The Reporter but in the middle of December the skies opened and Rockdale became what amounted to an island.

Cooke said the San Gabriel and Little Rivers were respectively “six and 12 feet higher than have ever been recorded.”

Train service stopped and the town was isolated from Wednesday through Sunday.

Cooke reported seven Rockdale men, in an attempt to reach the “outside world,” braved the high waters and got a railroad pump car through to Cameron on the San Antonio & Aransas Pass (SAP) tracks.

“But they gained nothing, as Cameron was as badly marooned as Rockdale,” Cooke wrote.

SKIFF - News reached Rockdale that people were drowning at Valley Junction and help was needed, fast.

Early that Friday morning someone came to Suess’s house and said a rescue train, one engine and a baggage car, was headed for Valley Junction from Taylor and would stop in Rockdale if anyone wanted to join.

Suess climbed into the baggage car. “I asked God to send me, to give me the necessary courage and spare my life,” he recalled.

They arrived. “It was a scene I will never forget,” he recalled. “There was a raging torrent of red, muddy water as far as the eye could see. I heard the crying out of people who were in treetops and atop shacks that could not stand the water much longer.”

The only craft the rescue party had with them was a light skiff - a small boat used for leisure fishing - and intended only for dead water, according to Cooke.

“It did not even have oarlocks, and it was constructed in a very fragile manner,” Suess said. “The first thing I did was make oarlocks from wood.”

Only Suess was willing to make a rescue attempt in the little boat. “Some told me you will never make it,” he said. Battling the current with every stroke, it took him almost three hours to reach Valley Junction.

“I was caught in a stiff swirl of current many times which caused me to face the place I had just left,” Suess said. “It was then I saw men kneeling and praying for my life.”

HOTEL - Suess, exhausted, crashed through the telegraph operator’s window in the Valley Junction train depot. The operator laid him on a table to regain his strength and Suess was able to re-enter the boat and make it all the way to the hotel.

“The first floor was under five feet of water,” he recalled. “On the second floor were pigs, chickens, dogs, cats and naked people. My own clothing, by this time was a pair of torn blue serge pants. Someone had built a fire and I was glad to get at it.”

Here, Suess picked up A. E. Stafford, fireman of the train which carried now-dead railroad official Henry Martin to the scene. “He was a strong man of tender heart,” Suess wrote. “He went with me to rescue people.” The two men paddled back into the flood. Several were rescued before dark that Saturday night.

An elderly man, identified only as “Henry,” was found stranded in a tree several hundred yards from the station and was pulled into the boat.

But the tree was near the railroad dump which created a suction and tremendous current which sucked in the little craft.

It took Suess three hours to paddle out of the current, saving the lives of all three men.

Suess said Henry was so crazed with fright he had to be tied into the boat with ropes. “It was scarcely big enough for three sane people, let alone a crazy man,” he told The Reporter later.

Somehow he guided the boat back to the hotel. Henry and Stafford were able to scramble inside but Suess was so exhausted, people inside the hotel had to pull him in through a window.

'AMAZED’ - Suess was “warmed and slept,” woke up the next morning (Saturday) and again he and Stafford set out in the skiff.

They went upriver for two miles, pulling men, women and children from the tops of houses and trees, carrying them back to safety.

The area around Valley Junction had some of the last plantations in Texas, using the rich Brazos bottomland soil for cotton, and all the persons rescued that day by Suess and Stafford were African Americans.

Some had been on rooftops, or in trees, for three days. “In some places we let our boat drift down to the place where the person was by means of a long rope, as in some places the current was stronger and we could not handle the boat with oars,” Suess recalled.

“The people we rescued were men, woman and children, mostly naked and not knowing it,” Suess said. “I was amazed at their patience and behavior.

“We piled them into the boat like sticks of wood and took them to a two-story barn that was strong and hoisted them up into the hayloft where they could get warm.”

RESCUED - By noon that day, with a total of 44 persons plucked from almost certain death, Suess and Stafford were exhausted, turned the little boat and headed upstream.

It took three hours to struggle upstream to safety.

“On attempting to get out of the boat, I fell over into the water,” Suess said. “With no strength left, I did not care whether I drowned or not.”

The rescuer was rescued. “The quick action of someone with a rope saved my life,” Suess said, “He and his companions were placed in a hack and taken to Gause where they were cared for and were soon all right,” Cooke wrote.

A special train from Austin arrived for the survivors. Suess was bandaged, cared for and, as he recalled, “made to rest.”

Cooke said Suess didn’t want any acclaim for what he had done, but promised to see if the Carnegie Hero Commission would recognize him.

“Rockdale is proud to own such a man,” Cooke wrote.

HERO - It’s doubtful if Rockdale ever produced anyone who was documented to have saved any more lives than the apparently mild-mannered plumber.

Suess was 28 at the time of his remarkable actions and left Rockdale soon after the flood to settle in San Antonio.

In 1920, he married Louise Estelle Stolz in Houston. By 1940 the family was living in Dallas. Suess had four sons and two daughters. One son, PFC. Roland Lonnie Suess, was a World War II casualty, dying in November, 1944, in Belgium.

Walter Suess died Sept. 29, 1958, in Dallas at age 73, and is buried in that city’s Oakland Cemetery.

In 1997 a daughter, Dorothea Suess Syperda, wrote “A Story of a Very Short Period of My Life,” about her father’s 1913 experience, which provided the quotes in this article.

“Through that night (in the hotel) we had heard the call(s) of distress,” Walter Suess recalled. “Friends, have you ever heard it, the sound can never be forgotten.”

by Mike Brown - Reporter Editor

Rockdale Reporter - December 19, 2013

Rockdale Plumber Saved 44 Lives in Devastating 1913 Brazos Flood

Christmas season “miracles” come from a variety of sources, but for 44 flood-stranded victims of the Brazos River 100 years ago one came from Rockdale.

Walter Suess, a Rockdale plumber, launched a light skiff into the roiling six-mile-long lake that had mostly consumed the community of Valley Junction, and brought them to safety.

The flood, together with the iconic 1921 event eight years later, is regarded as one of the two worst in Milam County history.

“Walter E. Suess, an humble citizen, quietly stepped forward when all others held back in awe,” Reporter Publisher John Esten Cooke wrote. “(He) placed his life in jeopardy when others more dangerously situated might be saved.”

The Gause area flood had already claimed the lives of three men, one of them Henry Martin, the vice-president and general manager of the International & Great Northern Railroad.

Martin had brought his personal rail car to the area to direct rescue operations.

Two Gause men, Willie Roberts and Tim Lee, drowned in a separate attempt to launch a boat into flood waters to rescue the dozens of persons in peril at Valley Junction, just across the river in Robertson County.

MAROONED - The central U. S. had already experienced a history-making flood on Easter Sunday, 1913, but in Texas the fall and winter were worse.

Several smaller floods had already been covered in The Reporter but in the middle of December the skies opened and Rockdale became what amounted to an island.

Cooke said the San Gabriel and Little Rivers were respectively “six and 12 feet higher than have ever been recorded.”

Train service stopped and the town was isolated from Wednesday through Sunday.

Cooke reported seven Rockdale men, in an attempt to reach the “outside world,” braved the high waters and got a railroad pump car through to Cameron on the San Antonio & Aransas Pass (SAP) tracks.

“But they gained nothing, as Cameron was as badly marooned as Rockdale,” Cooke wrote.

SKIFF - News reached Rockdale that people were drowning at Valley Junction and help was needed, fast.

Early that Friday morning someone came to Suess’s house and said a rescue train, one engine and a baggage car, was headed for Valley Junction from Taylor and would stop in Rockdale if anyone wanted to join.

Suess climbed into the baggage car. “I asked God to send me, to give me the necessary courage and spare my life,” he recalled.

They arrived. “It was a scene I will never forget,” he recalled. “There was a raging torrent of red, muddy water as far as the eye could see. I heard the crying out of people who were in treetops and atop shacks that could not stand the water much longer.”

The only craft the rescue party had with them was a light skiff - a small boat used for leisure fishing - and intended only for dead water, according to Cooke.

“It did not even have oarlocks, and it was constructed in a very fragile manner,” Suess said. “The first thing I did was make oarlocks from wood.”

Only Suess was willing to make a rescue attempt in the little boat. “Some told me you will never make it,” he said. Battling the current with every stroke, it took him almost three hours to reach Valley Junction.

“I was caught in a stiff swirl of current many times which caused me to face the place I had just left,” Suess said. “It was then I saw men kneeling and praying for my life.”

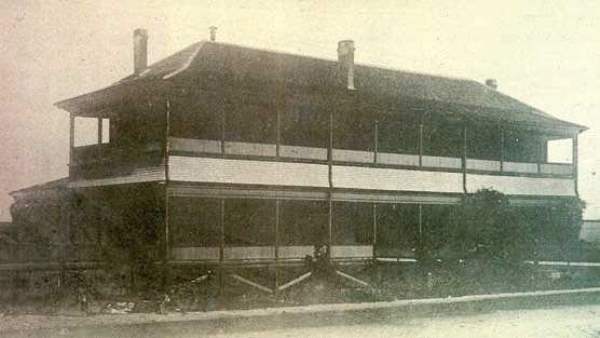

HOTEL - Suess, exhausted, crashed through the telegraph operator’s window in the Valley Junction train depot. The operator laid him on a table to regain his strength and Suess was able to re-enter the boat and make it all the way to the hotel.

“The first floor was under five feet of water,” he recalled. “On the second floor were pigs, chickens, dogs, cats and naked people. My own clothing, by this time was a pair of torn blue serge pants. Someone had built a fire and I was glad to get at it.”

Here, Suess picked up A. E. Stafford, fireman of the train which carried now-dead railroad official Henry Martin to the scene. “He was a strong man of tender heart,” Suess wrote. “He went with me to rescue people.” The two men paddled back into the flood. Several were rescued before dark that Saturday night.

An elderly man, identified only as “Henry,” was found stranded in a tree several hundred yards from the station and was pulled into the boat.

But the tree was near the railroad dump which created a suction and tremendous current which sucked in the little craft.

It took Suess three hours to paddle out of the current, saving the lives of all three men.

Suess said Henry was so crazed with fright he had to be tied into the boat with ropes. “It was scarcely big enough for three sane people, let alone a crazy man,” he told The Reporter later.

Somehow he guided the boat back to the hotel. Henry and Stafford were able to scramble inside but Suess was so exhausted, people inside the hotel had to pull him in through a window.

'AMAZED’ - Suess was “warmed and slept,” woke up the next morning (Saturday) and again he and Stafford set out in the skiff.

They went upriver for two miles, pulling men, women and children from the tops of houses and trees, carrying them back to safety.

The area around Valley Junction had some of the last plantations in Texas, using the rich Brazos bottomland soil for cotton, and all the persons rescued that day by Suess and Stafford were African Americans.

Some had been on rooftops, or in trees, for three days. “In some places we let our boat drift down to the place where the person was by means of a long rope, as in some places the current was stronger and we could not handle the boat with oars,” Suess recalled.

“The people we rescued were men, woman and children, mostly naked and not knowing it,” Suess said. “I was amazed at their patience and behavior.

“We piled them into the boat like sticks of wood and took them to a two-story barn that was strong and hoisted them up into the hayloft where they could get warm.”

RESCUED - By noon that day, with a total of 44 persons plucked from almost certain death, Suess and Stafford were exhausted, turned the little boat and headed upstream.

It took three hours to struggle upstream to safety.

“On attempting to get out of the boat, I fell over into the water,” Suess said. “With no strength left, I did not care whether I drowned or not.”

The rescuer was rescued. “The quick action of someone with a rope saved my life,” Suess said, “He and his companions were placed in a hack and taken to Gause where they were cared for and were soon all right,” Cooke wrote.

A special train from Austin arrived for the survivors. Suess was bandaged, cared for and, as he recalled, “made to rest.”

Cooke said Suess didn’t want any acclaim for what he had done, but promised to see if the Carnegie Hero Commission would recognize him.

“Rockdale is proud to own such a man,” Cooke wrote.

HERO - It’s doubtful if Rockdale ever produced anyone who was documented to have saved any more lives than the apparently mild-mannered plumber.

Suess was 28 at the time of his remarkable actions and left Rockdale soon after the flood to settle in San Antonio.

In 1920, he married Louise Estelle Stolz in Houston. By 1940 the family was living in Dallas. Suess had four sons and two daughters. One son, PFC. Roland Lonnie Suess, was a World War II casualty, dying in November, 1944, in Belgium.

Walter Suess died Sept. 29, 1958, in Dallas at age 73, and is buried in that city’s Oakland Cemetery.

In 1997 a daughter, Dorothea Suess Syperda, wrote “A Story of a Very Short Period of My Life,” about her father’s 1913 experience, which provided the quotes in this article.

“Through that night (in the hotel) we had heard the call(s) of distress,” Walter Suess recalled. “Friends, have you ever heard it, the sound can never be forgotten.”

All Credit for this article

goes to Mike Brown and the

Rockdale Reporter

goes to Mike Brown and the

Rockdale Reporter

Seven years after his heroism, Walter Suess wed Louise Stolz

When Suess arrived at the Valley Junction Hotel, the first floor was under five feet of water.

photo courtesy Robertson County Historical Society

photo courtesy Robertson County Historical Society

In December, 1913, wary Waco residents gathered at bridge to watch the Brazos flood their city.

photo courtesy the Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, Texas

photo courtesy the Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, Texas